Criminal Justice - Correctional Institutions

By Bradley Keen , Senior Budget Analyst | 4 years ago

Public Safety Analyst: Bradley Keen, Senior Budget Analyst

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections operates state correctional institutions (prisons) and secure community corrections centers. It also has limited oversight of county jails. Each year, thousands of inmates move through the system (in and out of county facilities, into state prisons and back out to local communities).

State correctional institutions (SCIs) hold individuals sentenced to a period of confinement with a maximum sentence of more than two years. Shorter sentences are served in county jails.

There are 23 state correctional institutions in Pennsylvania; one is for eligible participants in the motivational boot camp program and contains about 400 inmates, compared to about 1,600 in other SCIs. At its largest, from 2004 to 2012, the Department of Corrections operated 27 prisons, including the boot camp. In 2020, State Correctional Institutions held an average population of 42,360 inmates. In 2019, there were 15,991 admissions and 19,368 releases.

Newly sentenced inmates are assessed for programming and healthcare needs, security classification, and are then placed accordingly in a state prison. Each SCI provides healthcare, treatment, and educational programming in a secure setting. Certain SCIs provide additional specialized services such as geriatric care (SCI Laurel Highlands), psychiatric care (SCI Waymart), and programming for young offenders (SCI Pine Grove).

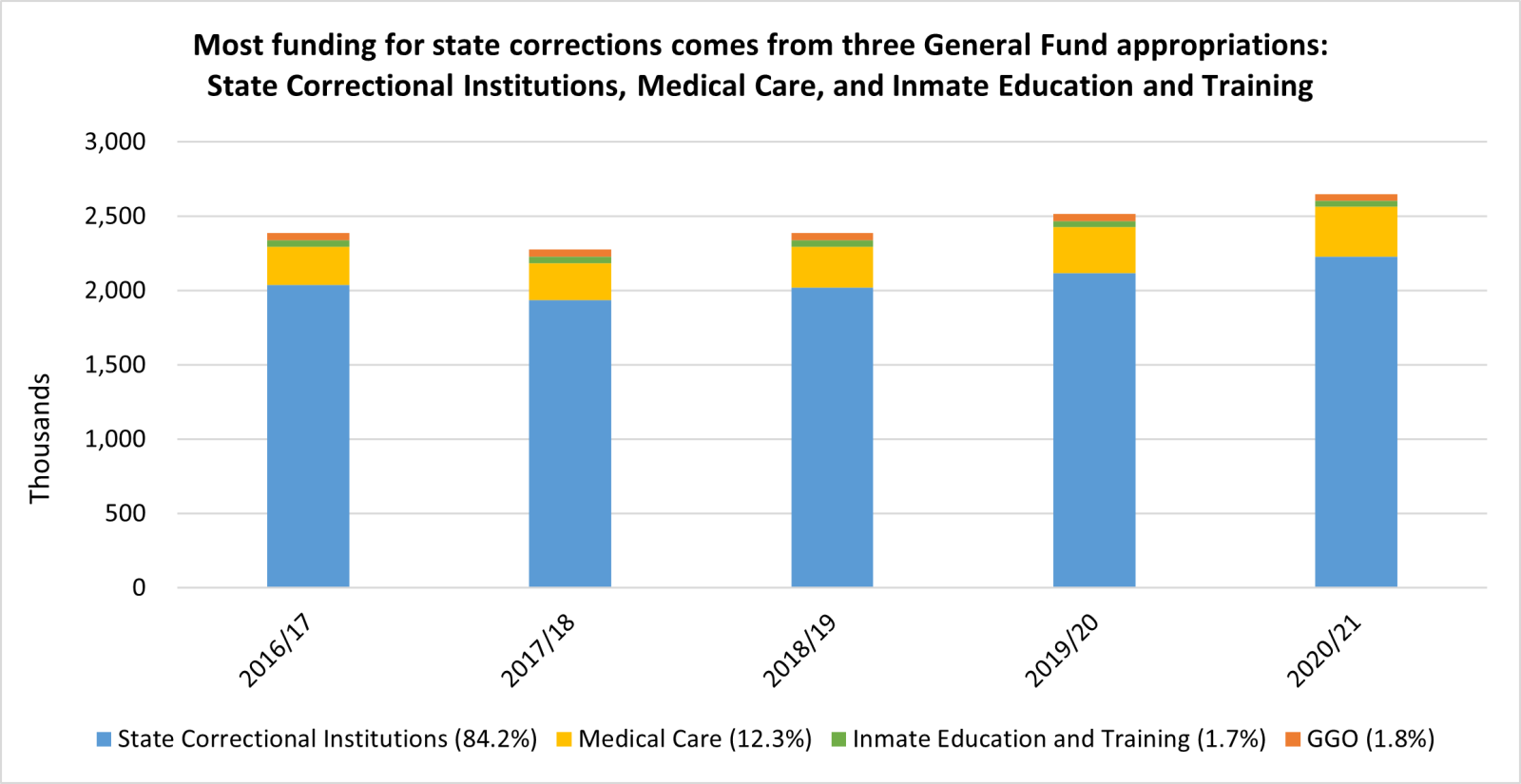

The majority of the above General Fund appropriations pay for state correctional institutions. General Government Operations (GGO) funds are used to support department and community corrections overhead.

Additional funding for SCIs comes from the federal government and the Manufacturing Fund. The manufacturing fund is a restricted account for Pennsylvania Correctional Industries, which is a bureau within the Department of Corrections that operates as a manufacturing company and job training program for inmates. PCI profits are deposited into the Manufacturing Fund, which, in turn, fully funds the program’s materials, equipment, staff compensation, and inmate pay. Under statute, use of the fund for these purposes is allowed as an executive authorization, meaning it does not require an annual appropriation.

Personnel

Personnel is the largest component of the Department of Corrections budget at 75 percent. State prisons, inmate education, field supervision, and the various boards and commissions are all predominantly driven by personnel costs.

Recent increases in personnel spending have been the result of retirement benefits, salaries, and health benefits. A dramatic rise in overtime -- reaching a high point in 2014/15 -- contributed to increased costs as well. Hiring freezes, military activations, and transporting inmates to a hospital for medical care can also affect overtime staffing.

Inmate Medical Care

Inmate medical care is another significant cost driver for correctional institutions. In 2020/21, inmate medical care made up $309 million, or 12 percent, of General Fund expenditures for state prisons. Medical care includes physical, mental health, and dental, as well as medication costs. The high cost of certain treatments and pharmaceuticals, and the increasing health needs of an aging inmate population contribute to high medical expenses.

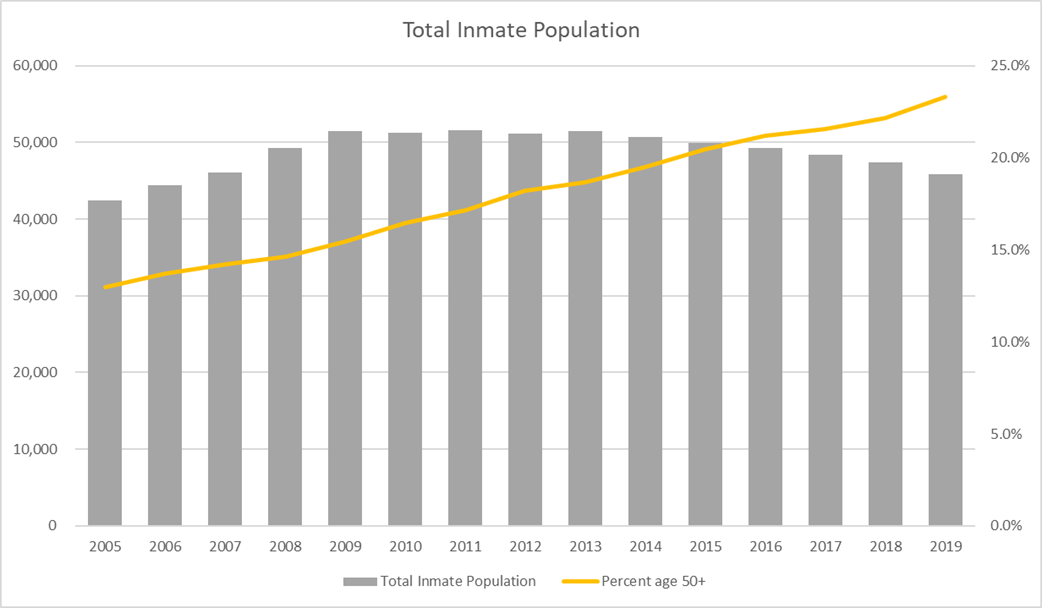

Demographic shifts also contribute to rising medical costs in state prisons.

Inmates over age 50 account for more than half of all the prison system’s pharmaceutical expenditures, although they are just 23 percent of the inmate population. Older inmates are more likely than other inmates to receive medications, and among those who do receive this medical attention, the average cost for medications is higher than younger inmates. Inmates over age 50 also use the majority of beds in skilled care units (a higher cost to the department due to more intensive staffing needs).

At SCI Laurel Highlands, where DOC provides geriatric care, the average cost for healthcare per inmate in 2019/20 was $22,454, which is more than three times higher than the average cost across all of the state correctional institutions.

The proportion of SCI inmates who are over age 50 has increased from 13.0 percent in 2005 to 23 percent today.

Healthcare is also more costly in prisons for women. The average cost per inmate in the two female SCIs is 21 percent higher than in male institutions. One contributing factor is a higher percent of women receiving mental health care compared to men (nearly double).

As of December 31, 2020, 5.6 percent of inmates in SCIs are women. In 2018, the inmate population at the two state prisons for women increased by almost 3 percent, while the male inmate population across the other state prisons fell by more than 2 percent. In 2019, however, both the male and female inmate populations decreased by approximately 3 percent.

DOC’s Bureau of Community Corrections oversees community corrections and reentry throughout the commonwealth.

There are three types of residential facilities where inmates transition from prison to the community or serve time for parole violations as an alternative to reincarceration in a state prison. Each facility may provide one or more types of programs, such as evidence-based reentry programming or licensed inpatient treatment.

- Community Corrections Centers (CCCs) are operated by the Department of Corrections to house DOC inmates in a residential setting. These centers allow inmates to participate in substance abuse treatment, work release, and other services. Offenders who are sentenced to the State Intermediate Punishment program, a drug treatment diversion program for state prisoners, begin in SCIs and then transition to CCCs or community contract facilities for the remainder of their sentence.

- Community Contract Facilities (CCFs) are facilities operated by private or non-profit entities. CCFs provide the same type of services as CCCs. Some CCFs also provide evidence-based programming in a residential setting for non-violent technical parole violators. Technical violations occur when an offender has broken the rules of parole but has not committed a new crime

- Contracted County Jails (CCJs) are county jails that have entered into a contract with DOC to house reentrants transitioning to the community or parolees who have committed a technical parole violation. Some technical parole violators, as defined in Act 122 of 2012, require a secure custody setting and, therefore, cannot be housed in CCCs or CCFs, but may only be housed in a CCJ or returned to an SCI.

County jails, also referred to as county prisons in Pennsylvania, differ from the state system because they house individuals who have not yet been sentenced (pre-trial), and inmates serving a maximum term of no more than two years, with some exceptions. Unlike state prisons, people churn through county jails. In Pennsylvania, the number of admissions and releases from county jails each year is about six times the inmate population at a single point in time.

Most counties operate a county jail, but five counties with lower populations (Cameron, Forest, Fulton, Sullivan, and Juniata) do not operate their own facilities. These counties pay a per diem fee to other facilities for inmates who would otherwise be detained in their jurisdiction. Juniata, in 2012, was the most recent county to close its jail in favor of boarding inmates in nearby facilities.

The Department of Corrections is responsible for annual inspections and reporting on county jails, but it has no enforcement authority. Although the commonwealth does not fund jails, some counties receive grants for programming from state agencies. One example is the Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) grant program, established by Act 80 of 2015. The grant program provided $1.5 million from DOC’s GGO to help counties implement MAT programs to combat opioid addiction. The funds were awarded to 13 counties in 2016 and continue to be annually earmarked in Fiscal Code legislation.

There is one private county prison in Pennsylvania: the George W. Hill Correctional Facility, operated by Community Education Centers (CEC is owned by GEO Group Inc.) in Delaware County since 1995 through a contract with GEO Group Inc. (then Wackenhut Corrections Corporation).

Although there are no private state prisons in Pennsylvania, some of the Department of Corrections’ Community Contract Facilities (CCFs) are operated by for-profit companies, including several operated by GEO Group. GEO Group and CoreCivic (formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America) are the two largest private prison companies in the United States.

Act 196 of 2012 established the Justice Reinvestment Fund as part of Pennsylvania’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative, which was designed to safely reduce state prison expenditures through a series of recommended policy changes (implemented in Act 122 of 2012), and to reinvest those savings in effective criminal justice initiatives.

A portion of the savings from the initiative was transferred annually to the Justice Reinvestment Fund by executive authorization, meaning no annual appropriation by the legislature was required. Over four years, $14 million was transferred into the fund and was then distributed for county probation, innovative policing, victim services, and other initiatives.

Acts 114 and 115 of 2019, also known as Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) 2, shifted $16.2 million from the Department of Corrections to the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency for the improvement of adult probation services. Additional funds will be deposited into the Justice Reinvestment Fund beginning in 2021-22 based on a percentage of program savings generated in the year prior to the deposits. Savings will be generated by the implementation of short sentence parole, increased use of the state drug treatment program, and the use of sanctions for technical parole violations.

According to the Department of Corrections, the JRI 2 package of bills will produce an inmate population reduction of approximately 600 inmates over its first five years, which translates to a cost savings of $44.9 million. Primarily these savings come from eliminating the State Intermediate Punishment program and replacing it with the more inclusive State Drug Treatment Program.

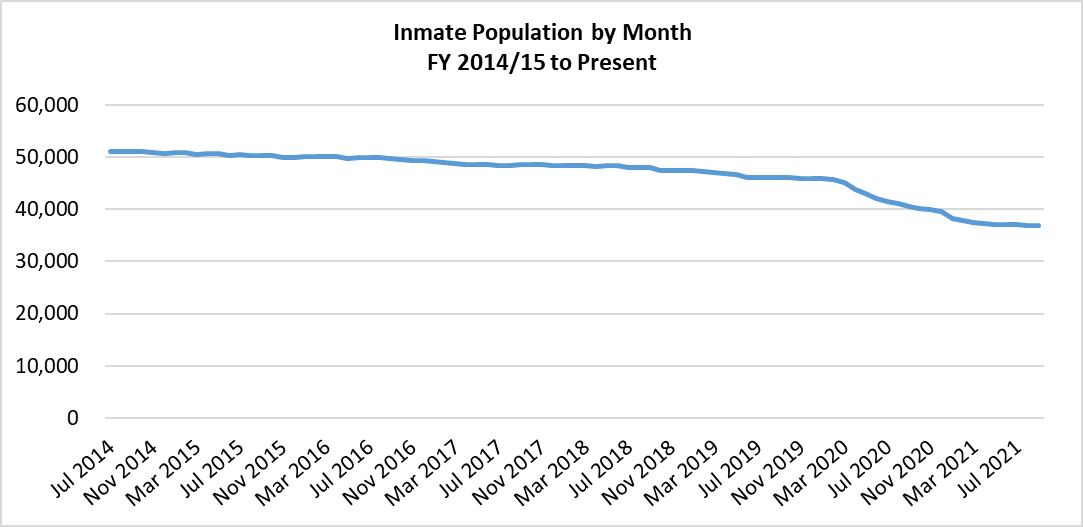

Safely reducing inmate population is the most effective way to achieve significant cost savings in correctional institutions. When the population decreases enough to close a housing unit (or increases enough to require opening one), there are significant changes in personnel expenditures. On a smaller scale, each inmate represents a marginal cost to the institution for items such as food, clothing, and medical care.

In Pennsylvania, the state prison population decreased annually beginning in 2010, aided by Justice Reinvestment Initiative reforms. At the same time, expenditures continued to increase because growth of prison costs outpaced savings from reducing the inmate population. That changed with the closure of SCI Pittsburgh in 2017, which contributed to a one-year decrease in annual spending.

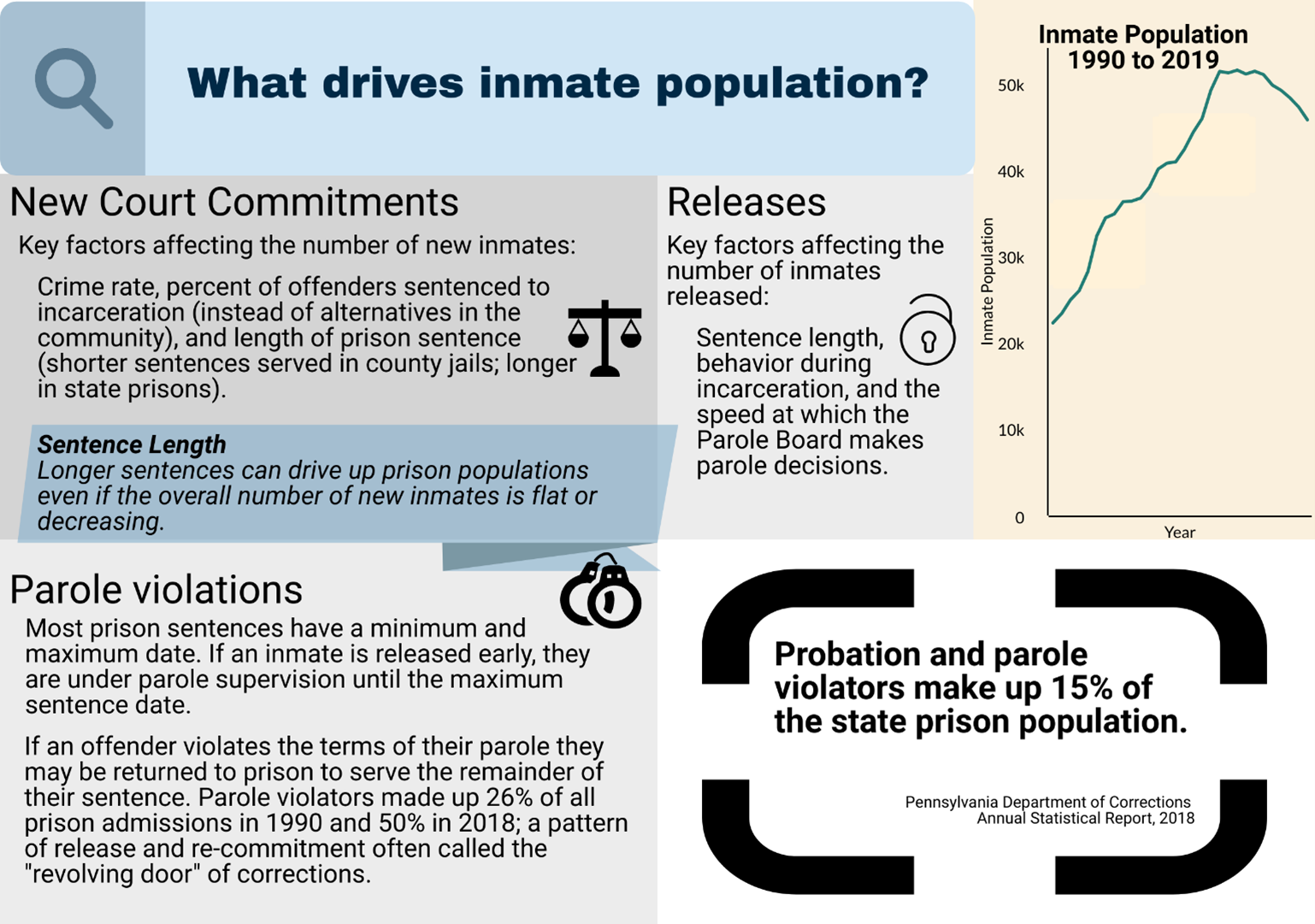

Inmate population is determined by court sentences, parole board release decisions, and individual behavior (crime, behavior in institutions, recidivism). The easiest of these factors for the legislature to directly influence is sentencing through the changing of laws that prescribe sentencing ranges, minimums, and enhancements. Other interventions – such as substance abuse treatment; job training; or Swift, Certain, Fair supervision programs – can be implemented by the Department of Corrections and Board of Probation and Parole.

DOC/PBPP Merger

In both legislative sessions of his first term, Gov. Wolf proposed to merge the Department of Corrections and Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole. A merger bill passed the Senate but did not receive a vote in the House. (SB 859 and SB 860 passed the Senate in Nov. 2015 37-10, and SB 522 and SB 523 passed the Senate in May 2017 38-12 and 48-2 respectively.)

Despite the lack of enabling legislation, the General Assembly appropriated funding as a single agency in the 2017/18, 2018/19, and 2019/20 General Appropriations Acts. The fiscal code included language clarifying that appropriations to the new department should be considered as appropriations to the existing, separate departments.

On Oct. 19, 2017, the DOC and PBPP signed a memorandum of understanding that formally consolidated several administrative functions, created a new organizational structure, and established a project charter and timeline to consolidate the two agencies over the course of a year.

Importantly, the Parole Board retains autonomy and full control over the parole decision-making process under the proposed legislation and the MOU.

Act 59 (Senate Bill 411) of 2021 finalized the consolidation of the Department of Corrections and the Board of Probation and Parole. It is estimated that the final passage of this legislation will save the department $10.5 million through 2023/2024 due to increased capacity in the State Drug Treatment Program (STDP) and a decline in overtime for transportation-related duties.

Terms and Definitions

Average Cost – The average annual cost per inmate, calculated by dividing total expenditures by inmate population (average daily population). Average annual cost is a useful tool for comparing the relative cost of different institutions or different types of confinement. (See also: Marginal Cost)

Average Daily Population – A common method of reporting inmate population in correctional institutions, calculated by averaging the inmate population on each day in a year. ADP differs from other monthly population averages, or year-end population counts because it accounts for population change throughout the year and can be scaled up (by multiplying by 365 days in a year) to give an accurate count of occupied bed days in a year.

Executive Authorization – An executive authorization is an expenditure authorized by the governor that does not require annual appropriation by the legislature during the budget process because it was previously appropriated by a blanket action of the legislature.

Marginal Cost – A method of reporting the cost per inmate that estimates the additional costs (or savings) generated by one more inmate assuming a total change in inmate population of a specific size. For example, larger population changes that require opening up a new housing unit and increasing the number of officers on duty will have a higher marginal cost than a small population change that only requires extra food, laundry, and other minor costs. Marginal cost is an effective tool to estimate the fiscal impact of inmate population changes caused by new policies or legislation.