Higher Education Primer

By Eric Dice , Assistant Executive Director | 5 years ago

Higher Education Analysts: Sean Brandon - Assistant Executive Director , Emma Eglinton - Budget Analyst

Pennsylvania’s diverse higher education sector - consisting of both public and private colleges and universities - helps students gain the knowledge and skills they need to pursue their ambitions. Because educated citizens are crucial to the commonwealth’s vitality, the people of Pennsylvania annually invest sizable budgetary resources in the form of institutional support and financial aid grants, which help to make a quality postsecondary education more affordable.

This briefing surveys the different types of higher education activities supported by the commonwealth and looks at budgetary trends. Over the years, the General Assembly has not used a consistent methodology to distribute funding between the different types of institutions. However, change may be on the horizon. Act 70 of 2019 established the Public Higher Education Funding Commission, which will examine a host of higher education-related goals, issues, and metrics to recommend a formula to distribute state appropriations to public institutions.

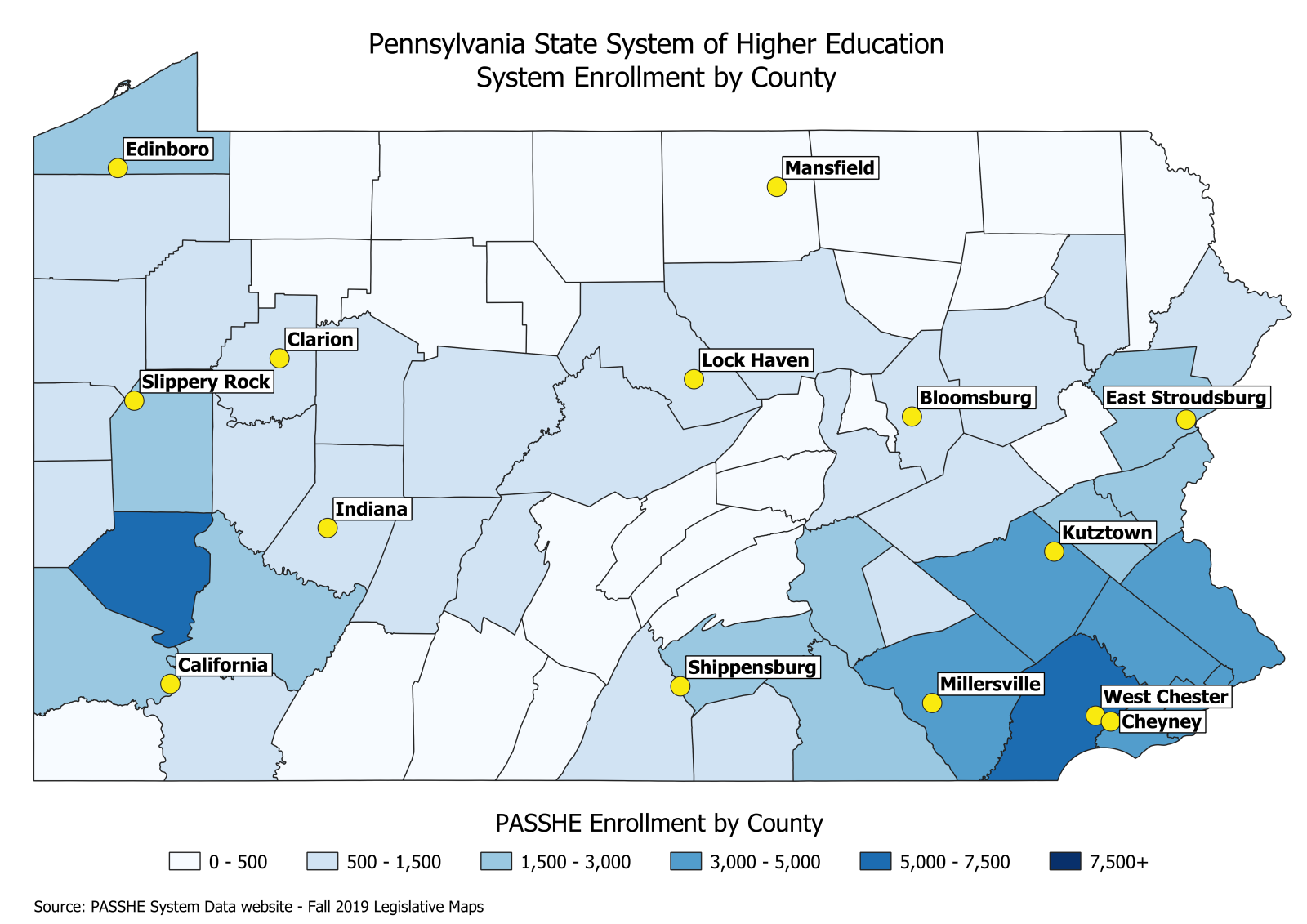

Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education

The Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education consists of 14 state-owned universities across the commonwealth. Formally established in 1982 by Act 188, PASSHE’s purpose is to provide high quality education at the lowest possible cost to students. Many of the system’s institutions were initially set up to train teachers and evolved into state colleges and universities that now offer a wide range of associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees, as well as limited doctoral programs.

In recent years, the General Assembly has made a single annual appropriation to the system in the General Appropriations Act; PASSHE then distributes the support to member universities through a formula set by the system’s Board of Governors. The formula accounts for factors such as enrollment, instructional costs, support services, and building and grounds costs.

The 14 PASSHE universities are:

- Bloomsburg University

- California University of Pennsylvania

- Cheyney University

- Clarion University

- East Stroudsburg University

- Edinboro University

- Indiana University of Pennsylvania

- Kutztown University

- Lock Haven University

- Mansfield University

- Millersville University

- Shippensburg University

- Slippery Rock University

- West Chester University

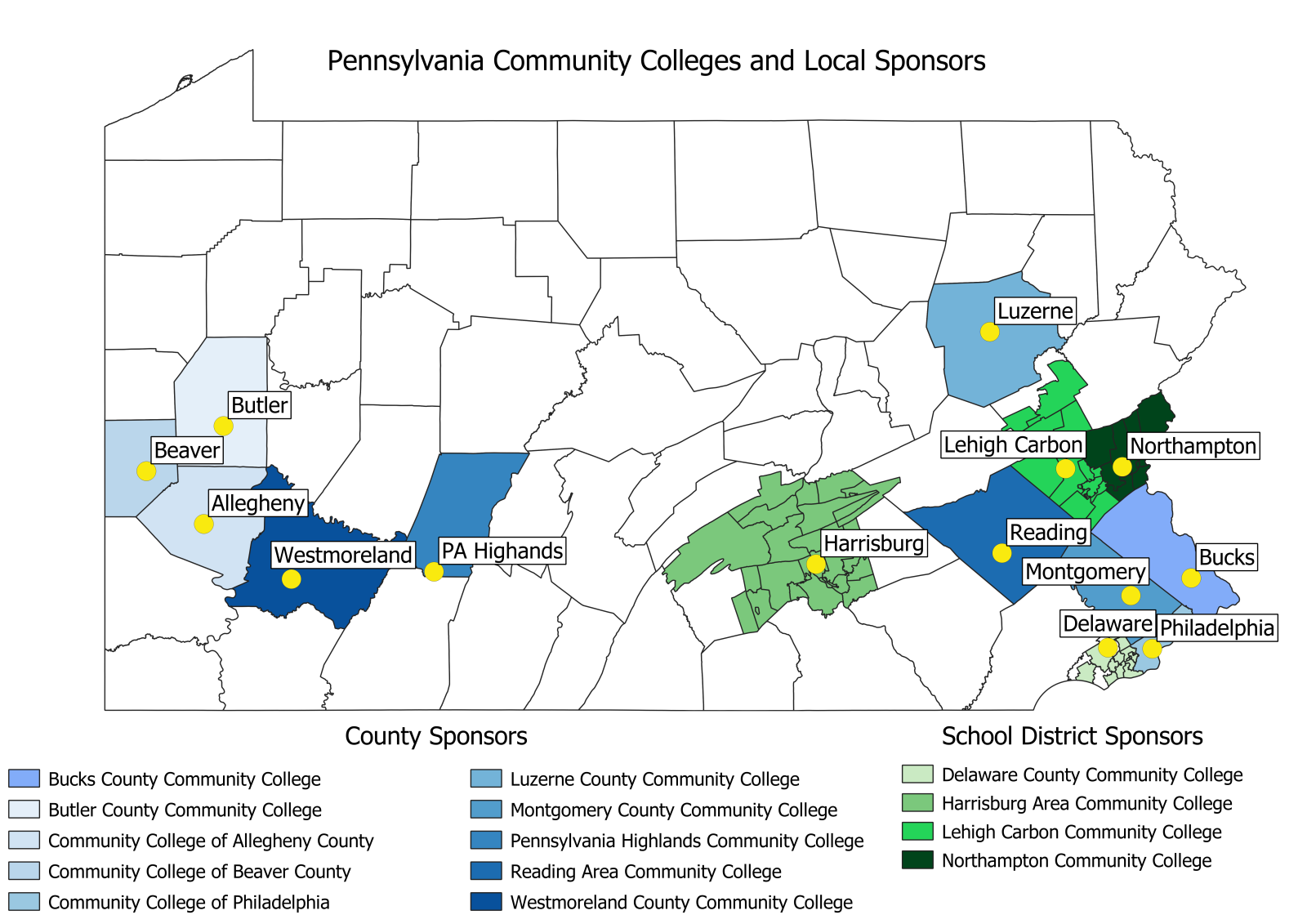

Community Colleges

Community colleges offer two-year and non-degree programs and were designed as a partnership between the state and local sponsors to make higher learning more affordable for students. Community college local sponsors tend to be county governments, although some are supported by groups of school districts. Students who reside in a sponsored area pay lower tuition than students from a non-sponsored location.

The Pennsylvania Department of Education distributes community college funding in the budget through a grant program, and the distribution formula is usually set each year by budget implementation legislation.

The 14 community colleges are:

- Community College of Allegheny County

- Community College of Beaver College

- Bucks County Community College

- Butler County Community College

- Delaware County Community College

- Harrisburg Area Community College

- Lehigh Carbon Community College

- Luzerne County Community College

- Montgomery County Community College

- Northampton Community College

- Community College of Philadelphia

- Pennsylvania Highlands Community College

- Reading Area Community College

- Westmoreland County Community College

The commonwealth does not have full geographic coverage with its community colleges, meaning many students in different parts of the state do not have access to this mode of learning, despite the need. Erie County in northwestern Pennsylvania is moving forward to establish a new community college. The State Board of Education approved Erie County’s community college plan in June 2020 -- the first community college to be approved in 25 years in Pennsylvania.

In response to some of the challenges in creating new community colleges, the General Assembly passed legislation in 2014 to establish a “rural regional college” similar to a community college but without the requirement for local sponsor support. This new institution, the Northern Pennsylvania Regional College, began operations in 2017, combining open enrollment with a remote delivery model. The college has no main campus, and courses are simulcast to different sites across a nine-county region in northwestern Pennsylvania. Currently, the college offers six associate’s degrees, one certificate program, and a number of non-credit workforce development programs.

Community education councils are another effort to try to help fill the regional gaps of full community colleges in certain parts of the state. CECs are non-profit organizations that act as facilitators and brokers of employer-driven educational programs, working to help get needed educational programs to students in the area in partnership with other colleges and universities. Community education councils receive state support through a specific appropriation to the Pennsylvania Department of Education, which distributes the grants to the councils.

Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology

Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster is a two-year technical college owned by the commonwealth. Originally founded in 1905 to serve orphans, the college now provides associate’s degrees in 22 high-skill technical education programs and five certificate programs to help meet workforce needs with special emphasis on serving economically and socially disadvantaged students. Thaddeus Stevens College is funded as part of the General Appropriations Act each year.

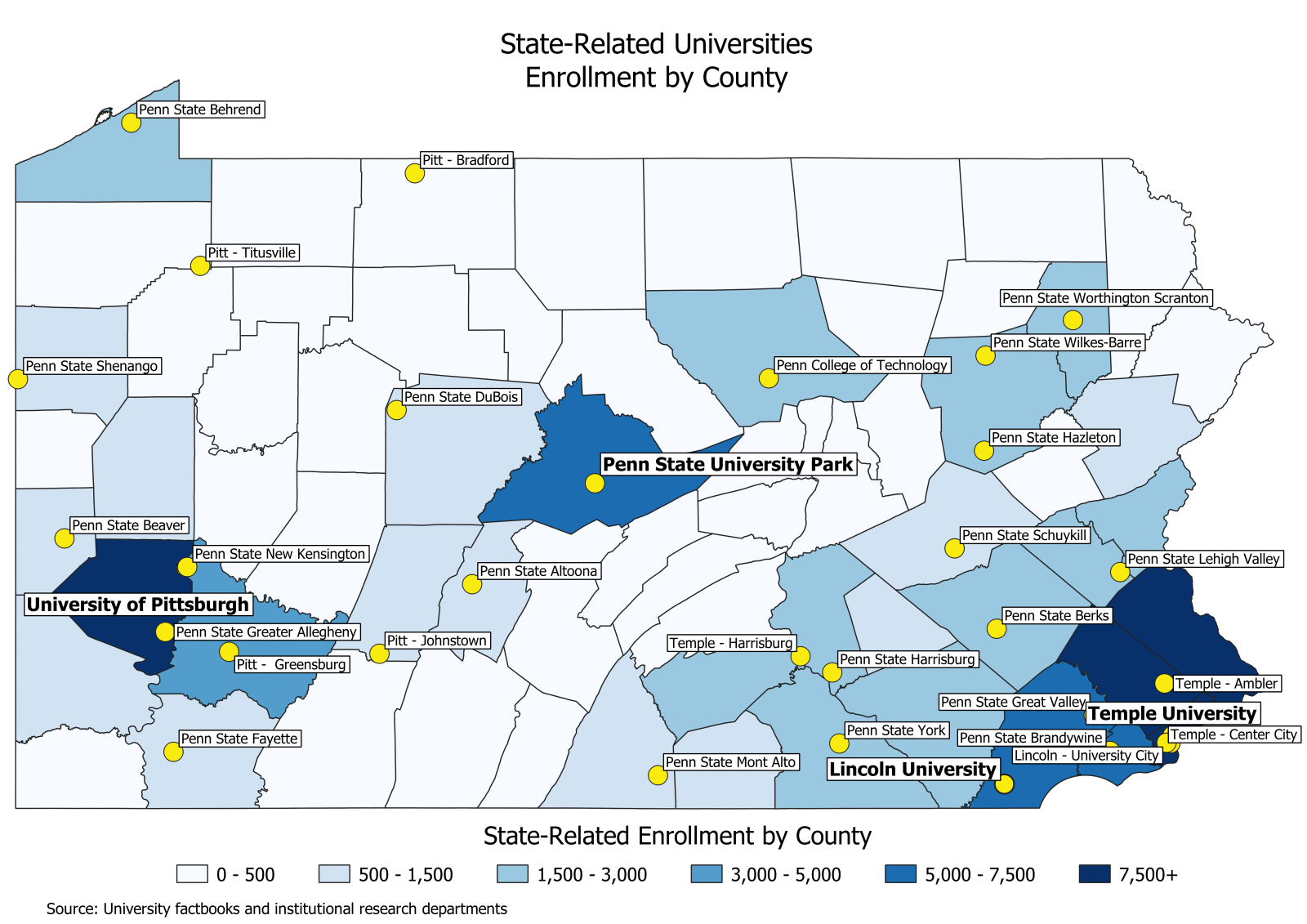

State-Related Universities

Pennsylvania has four universities that, while not owned by the commonwealth, have a special status conferred by law. These “state-related” universities receive direct appropriations and, in turn, offer in-state tuition rates for Pennsylvania students.

Penn State University, the University of Pittsburgh, and Temple University are major research universities. The fourth, Lincoln University, is a historically Black university in Chester County and is the oldest degree-granting historically Black institution of higher education in the United States.

The state-related universities operate branch campuses in different areas of the commonwealth. Penn State, in particular, has a large network of campuses statewide. While many students study at a branch campus and transfer to the main campus to complete their studies, full four-year programs are also offered at some locations.

The direct appropriations to the state-related universities fall into a special category called non-preferred appropriations. Under the Pennsylvania constitution, any direct appropriation to an educational or charitable institution not under the absolute control of the commonwealth is subject to more stringent rules. Such appropriations must be made in separate bills and receive a two-thirds vote from each chamber of the General Assembly to become law. Currently, there are five institutions that receive non-preferred appropriations: the four state-related universities, and the University of Pennsylvania, which receives support to operate the only veterinary school in the state.

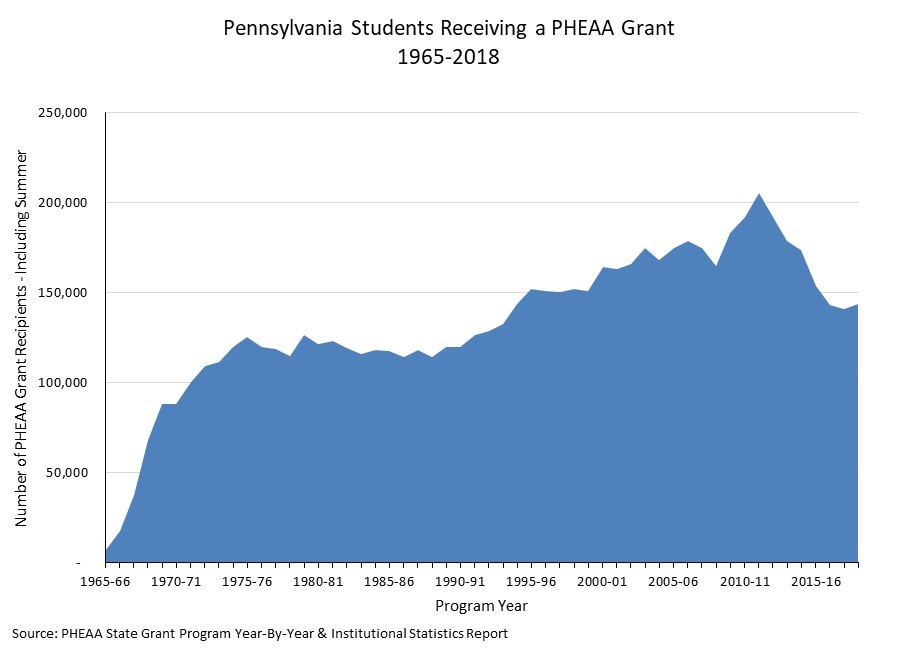

Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA)

Since 1963, the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, or PHEAA, has helped students pay for college with grants, loans, and work-study opportunities and is one of the largest student financial aid organizations in the country.

Through its subsidiaries and contracts with the federal government, PHEAA provides student loan servicing and financial aid services to students in many states. The agency also is a lender, offering undergraduate, graduate and parent loans to help finance postsecondary education, separate from federal student loans. The business earnings from these activities pay for administrative costs and, in some years, have helped subsidize the state-funded programs the agency oversees.

The largest PHEAA offering is the state grant program, which provides money to students who demonstrate financial need and attend a PHEAA-approved postsecondary institution. To qualify for aid, students must be Pennsylvania residents and enrolled at least half-time. Over 143,000 Pennsylvania students received a PHEAA state grant in the 2018/19 program year.

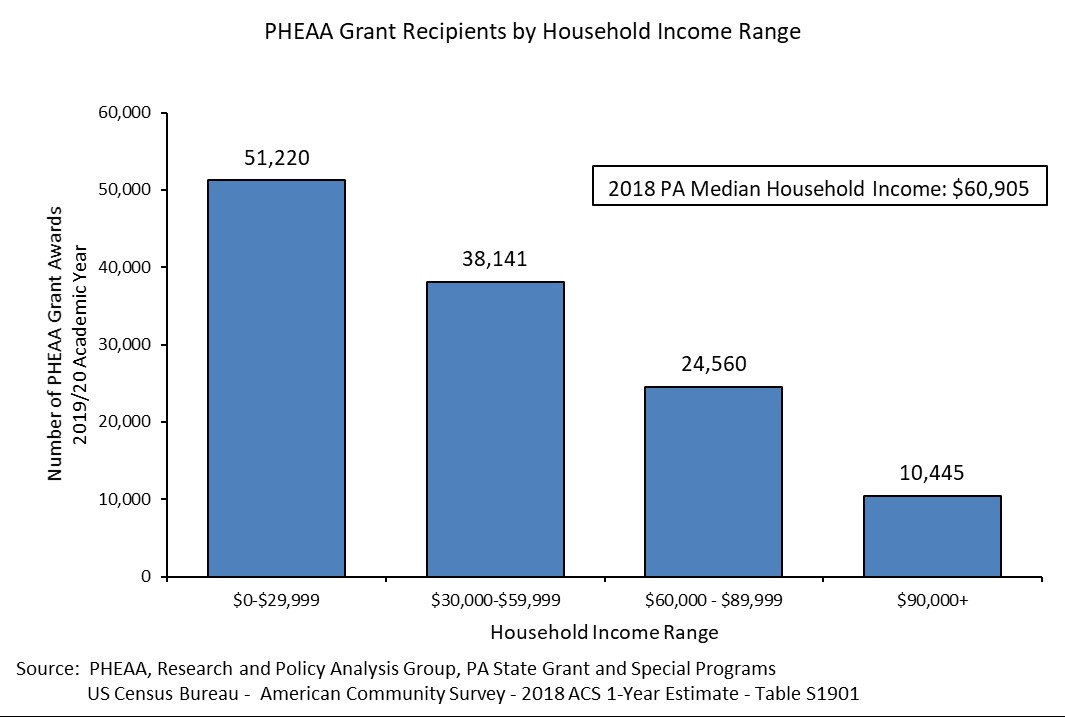

Aid primarily goes to students whose families earn less than the median household income, consistent with the program’s need-based philosophy. Around 72 percent of students who received a PHEAA grant during the 2019/20 academic year were from households who earned less than the statewide median household income.

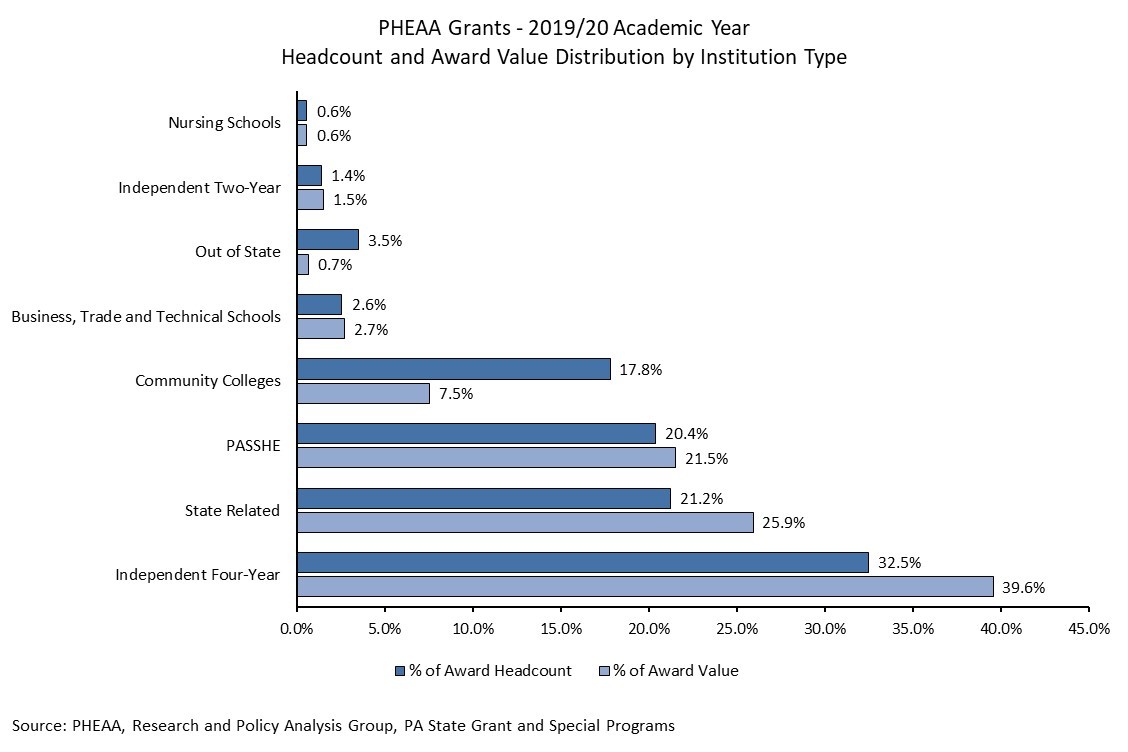

In 2018, the General Assembly expanded the grant program to include distance education students who take more than 50 percent of credits online. Award amounts vary each year with the amount of funds appropriated, the number of eligible students applying, the financial need of the student, and the type of institution a student attends. Additionally, the PHEAA board can implement separate cost controls for grants for distance education students.

For a number of years, PHEAA’s business earnings contributed significant additional funds to augment state appropriations and expand the amount of aid available under the state grant program. Business earnings also supported the Pennsylvania Targeted Industry Program (PA-TIP), which provides grants to students enrolled in approved certificate programs in high-priority industries that are less than two years in length; and the Primary Health Care Practitioner Loan Repayment Program, an incentive to attract medical professionals to underserved areas. However, PHEAA’s ability to subsidize program costs depends on the health of its business side. This challenge, and its impact to the state appropriation, is discussed later in this document.

The General Assembly created the Ready to Succeed merit-based grant program in 2014 for outstanding students whose annual family income does not exceed $110,000. Students can receive up to $2,000 annually, often as a wrap-around award along with a state grant. The Ready to Succeed scholarship’s appropriation is small compared to the existing state grant program, but the merit-based approach is a departure from the traditional need-based state grant program.

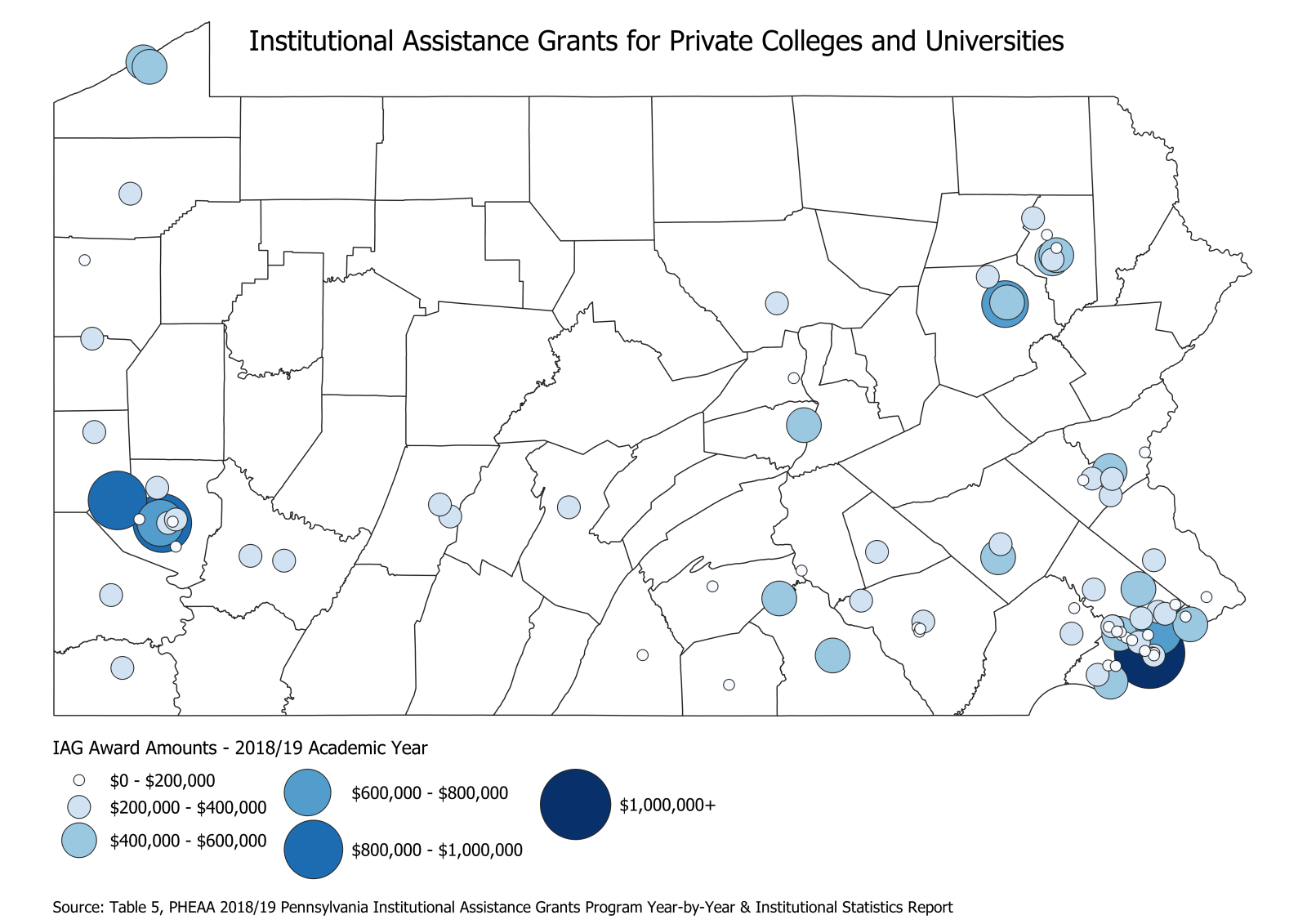

Institutional Assistance Grants for Private Colleges and Universities

Although it makes up a comparatively small part of direct institutional support, Pennsylvania has a program to help more than 80 private institutions.

Non-profit, non-denominational colleges and universities that are not state-owned, state-related or a community college and do not receive direct state aid through a non-preferred appropriation are eligible to receive an institutional assistance grant from PHEAA. Grants are distributed based on the number of students who receive individual PHEAA state grants at eligible schools. Once a per capita amount is determined, each school receives its apportionment based on the number of PHEAA grant recipients enrolled at the institution.

Grants are made to the institution, not the student, although many schools use them to help augment student financial aid packages.

Other University Activities and Special Circumstances

Because of the breadth of activities with which they are involved, universities often intersect with other parts of the state budget.

Some universities with academic medical centers and other teaching hospitals receive funding through the Department of Human Services as part of the Medical Assistance budget.

As Pennsylvania’s land-grant institution, Penn State University has an important role in supporting agriculture in the state. It receives funding for agricultural research and for its county extension offices. These programs help bring cutting-edge research into the field and help farmers and other agricultural industries be more productive and efficient.

Along with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s State Veterinary Laboratory, the commonwealth leverages two university-based facilities as part of its Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Laboratory System (PADLS). The Penn State Animal Diagnostic Laboratory and the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center help perform animal health, research, and diagnostic programs. This partnership helps ensure that Pennsylvania maintains rapid and precise diagnostic capabilities to deal with animal-related disease outbreaks and ensure a safe food supply.

The University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine is the only veterinary institution in the commonwealth. Penn Vet has educated the majority of practicing veterinarians in the commonwealth and delivers research and medical solutions to the agricultural industry.

From time-to-time, policymakers address special circumstances with other appropriations in the state budget. For example, the General Assembly appropriated money to help pay for the installation of fire sprinklers in dorms following the Seton Hall fire in 2000.

Capital Funding

Capital funding helps institutions with their buildings and infrastructure needs. The way in which the commonwealth helps institutions varies by sector. Generally, for its public four-year institutions, Pennsylvania uses general obligation debt to provide capital allocations to the institutions or system, depending on the type of university (e.g., state-related or PASSHE). The institution retains autonomy to make project decisions. Community colleges receive debt service support subsidies for approved projects from the state’s operating budget.

The PASSHE universities also receive dedicated funding for deferred maintenance through a portion of the realty transfer tax as part of the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund (Key ’93). This funding also flows from the commonwealth to the system, and then is allocated through a formula by the Board of Governors to the universities.

Budgetary Trends

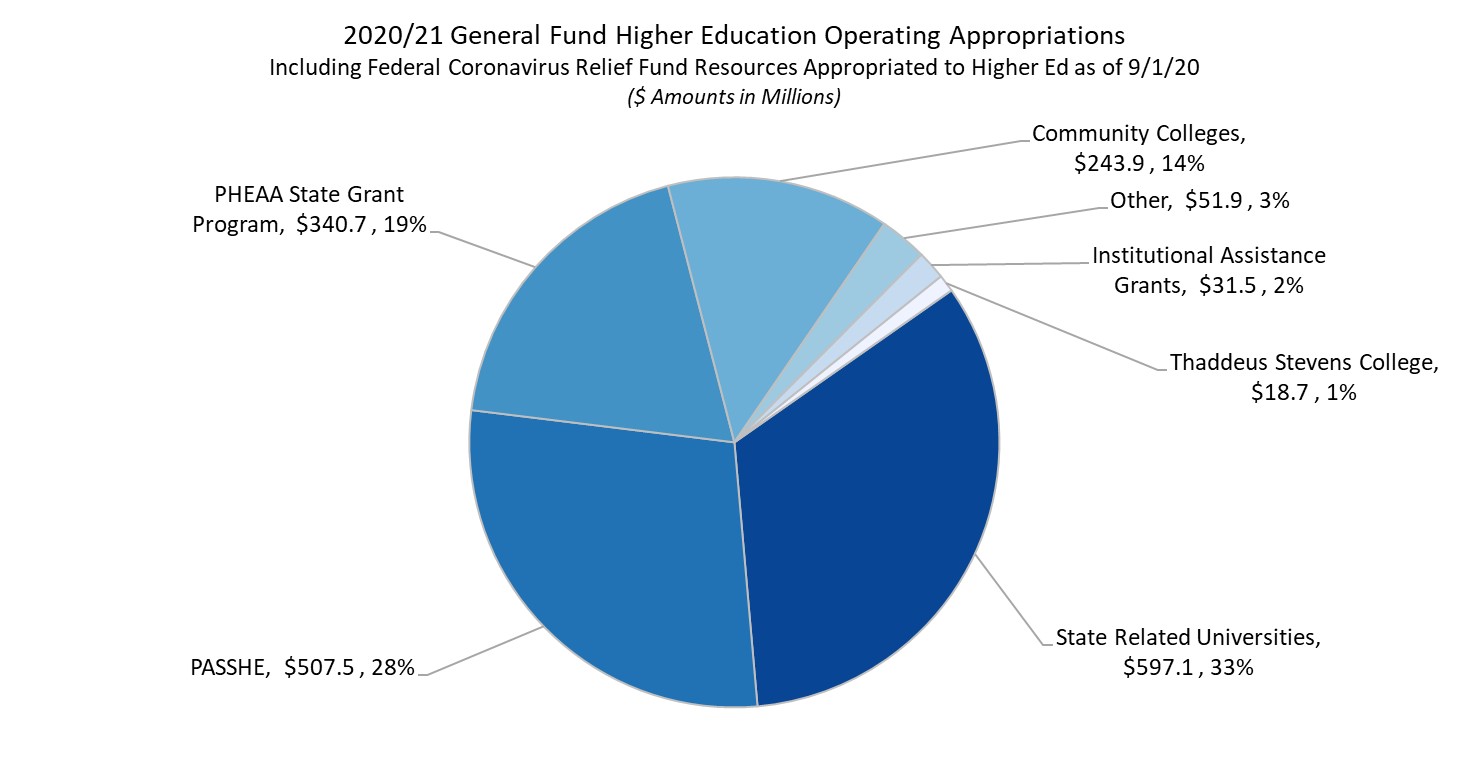

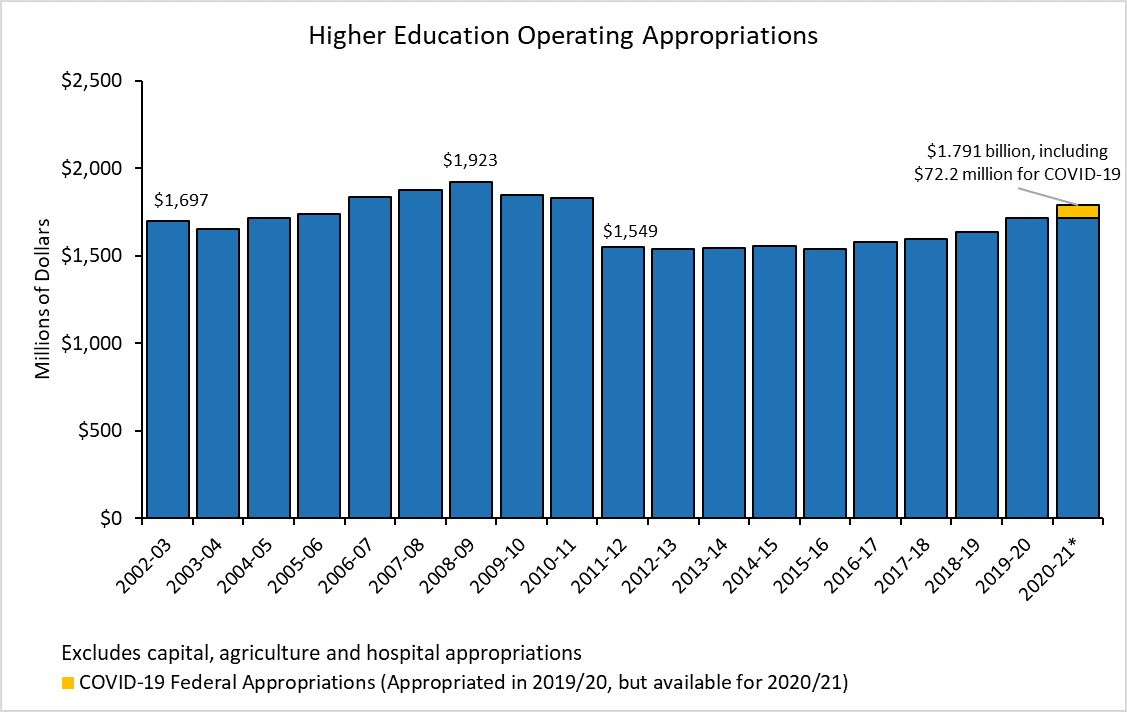

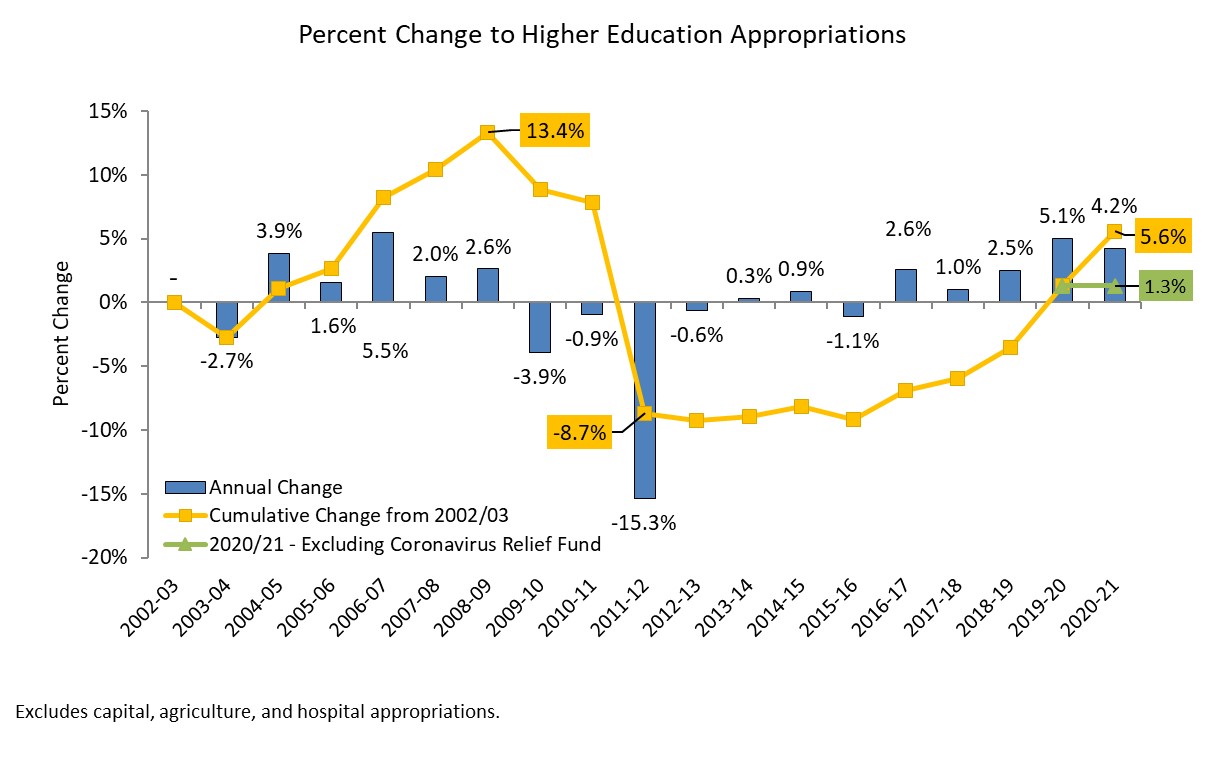

Higher education operating appropriations from the General Fund were just over $1.7 billion in 2020/21. Adding to this total, the General Assembly appropriated $72.2 million in federal Coronavirus Relief Fund dollars, which Congress made available to states to help respond to challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the legislature technically appropriated these resources as a supplemental appropriation for the 2019/20 fiscal year, in practice they are available to support the 2020/21 fiscal year and are shown this way in the following graphs and charts.

This total includes all operating appropriations for community colleges, PASSHE, state-related universities, Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology, community education councils, regional community college services, and all appropriated PHEAA programs, but excludes community college capital, non-appropriated PHEAA business earnings, and other activities like the University of Pennsylvania veterinary school, agriculture-related transfers to Penn State, and medical school appropriations.

Looking at appropriations trends over the years can be difficult because many different things have been grouped under “higher education” in the past. As time passed, the funding mechanisms have changed as well, with appropriations being moved to different departments and into special funds.

To compare apples to apples, the following chart focuses on operational funding by excluding capital funding, agricultural support, PHEAA business earnings and medical-related appropriations. It includes federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act appropriations from 2008/09 through 2010/11 that supplemented operational funding. For the 2020/21 fiscal year, it includes federal Coronavirus Relief Fund appropriations allocated to higher education by the General Assembly.

Higher education comprises one of the largest areas of discretionary spending in the General Fund budget. As a result, the sector is more susceptible to cuts during economic downturns and in times of budgetary pressure.

While support increased in the years leading up to the Great Recession, significant cuts were made during and immediately after the Great Recession, most notably in 2011/12. Overall expenditures remained essentially flat from 2012/13 through 2015/16.

In 2015/16, though institutions saw increased appropriations ranging from 3-5 percent, PHEAA’s appropriation declined. The impact of that reduced appropriation was offset, in part, by a greater reliance on business earnings.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused another recession, and the effect of this latest economic downturn on Pennsylvania’s higher education has not yet fully manifested. The General Assembly passed a partial interim budget in May 2020 for the 2020/21 fiscal year. This budget provided flat funding for state appropriations for the entire fiscal year, plus an additional $72.2 million in federal funds for COVID-19 response. The final budget enacted in November maintained level higher education funding for the fiscal year. Even though the budget contained no cuts to higher education appropriations, all sectors face lost revenue and increased costs due to the pandemic. As has been the case in previous recessionary periods, the commonwealth’s budget pressures in mandatory areas likely will make it difficult to provide additional support to non-mandatory programs like higher education.

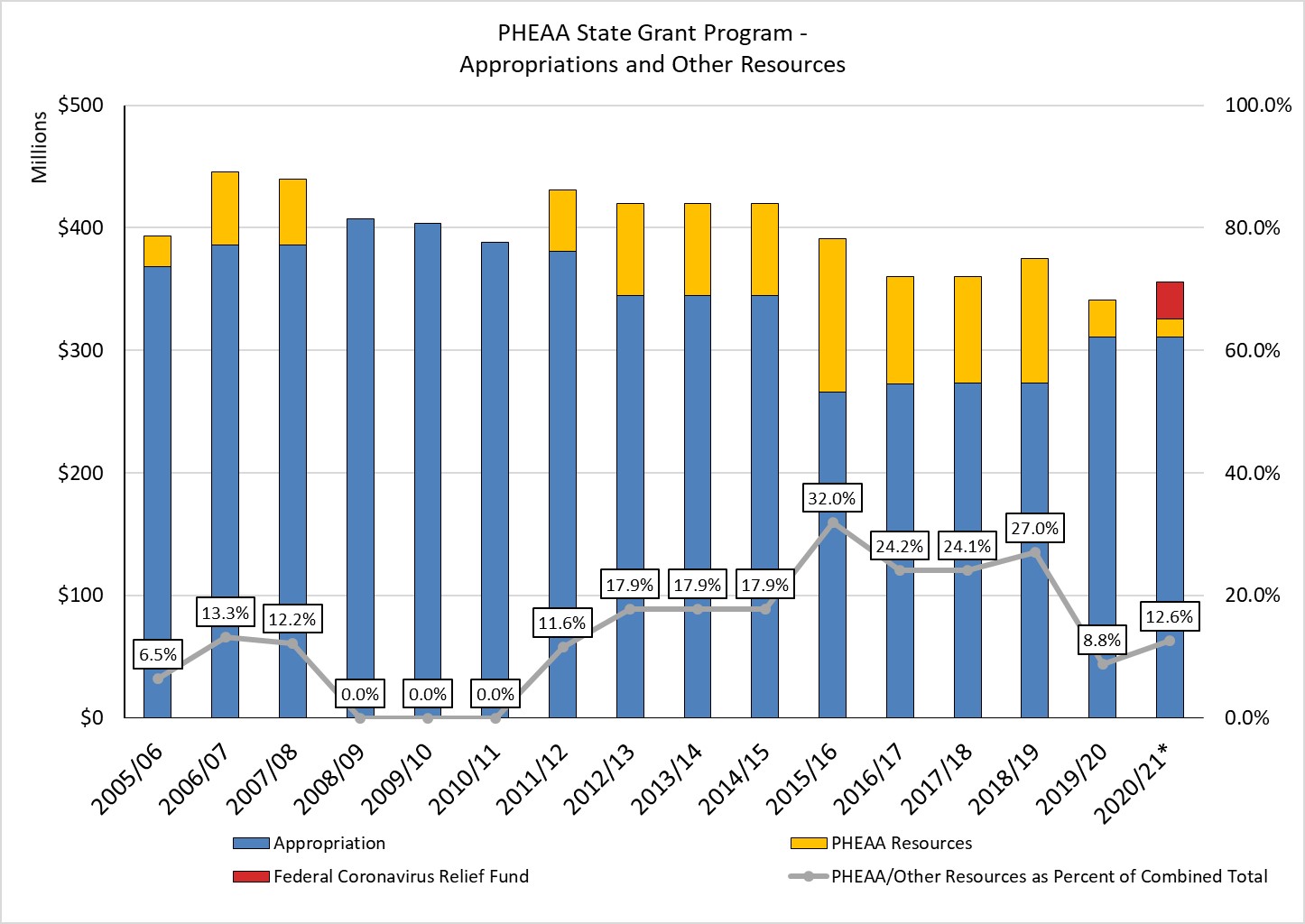

Pennsylvania used part of its federal Coronavirus Relief Fund resources in 2020/21 to provide additional need-based aid to students through PHEAA grants. While providing important help to students in a period when many families face additional financial hardship, these federal dollars are a one-time funding source. It also continues a recent period of increased reliance on resources other than the state appropriations.

In some years, PHEAA has been able to use its business earnings to augment the state appropriation for PHEAA grants. Of the total amount provided by business earnings and General Fund appropriations, PHEAA’s resources comprised almost one-third of the amount in 2015/16 and around 27 percent in 2018/19, but did so amidst declining net income at the agency. A cautionary example of what can happen when PHEAA is unable to contribute additional resources comes from 2008/09 to 2010/11, when underlying business pressures on PHEAA precluded any augmentations and dramatically reduced the total pool available for student aid, amidst growth in the number of students who qualified for a grant.

The 2019/20 fiscal year once again saw a significant reduction in the amount of augmentations due to increased financial pressure on PHEAA. In response, the General Assembly increased the state grant appropriation by $37.3 million, or 13.7 percent. The additional appropriated resources, along with a smaller applicant pool and carryforward resources were able to maintain the maximum state grant award, year-over-year.

The General Assembly appropriated $30 million in Coronavirus Relief Fund dollars to augment PHEAA grants. This temporary boost from federal resources is likely to disappear next fiscal year, meaning policymakers will once again need to evaluate the impact to students from changing non-appropriated funding streams.

Higher education funding in Pennsylvania encompasses many different institutions and agencies. The different sizes, missions, student bodies served, goals, and governance structures, makes allocating resources between the different types of institutions a challenge, especially because the public institutions are not organized under a cohesive system. However, this process may improve in the coming years.

Act 70 of 2019 established the Public Higher Education Funding Commission. The nineteen-member commission is comprised sixteen legislators from the General Assembly, including the four Appropriations Committee chairs, the four Education Committee Chairs, and two additional members from each legislative caucus, plus the Secretary of Education, the Deputy Secretary for Postsecondary and Higher Education, and another individual appointed by the governor. The commission is charged with developing a higher education funding formula and identifying factors that may be used to distribute funding among the public institutions of higher education, such as goals for higher education, enrollment, access, affordability, cost, student debt, institutional missions, and outcomes. The commission will look for efficiencies and consider how a formula could impact each public institution of higher education.

The commission began its work last fall and held three hearings between October 2019 and February 2020 to start to gather information. However, the pandemic disrupted this work, and Act 30 of 2020 delayed the commission’s report until November 30, 2021.